China (103)

Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur.

Golden Rock Meditations, Kyaiktiyo Myanmar

I took the first day at Camp Kinpun with ease while awaiting the pilgrimage up the mountain to the the Kyaiktiyo Golden Rock. I arrived at 4pm, check into a nearby hotel, and so I wander aimlessly through the town. They call it a camp because it's a small village made with straw huts, nat temples, small shops, etc; although, it isn't meant to be a permanent establishment but serve the purposes of pilgrims. There are several people selling Myanmar "sandalwood" which is actually thanaka. The wood is beautiful smelling so I buy a mala and a few blocks of it. There are also vendors selling foods, bamboo toy guns with a clever crank handle. The "candy stores" were incredible, selling dried fruits, many of which were candied; durian paste, dates, marion berries, and coconut candies. There is a nice amount of commercialization for local crafts and clothes near the rock. I decide to buy some candles and incense to offer to the golden rock, which costs me about 0.50c.

The next morning, I woke up at sunrise and the Burmese foods in my stomach sat heavily. The cooking here uses a lot of oil, and even salads are covered with oil; pennywort salad, fermented tea leaf salad, and vegetable fried rice. I noticed it immediately, but I didn't want it to hold me back from the early morning rise I was anticipating. The bus station is full of ready pilgrims at 5:30am. It seems that I'm rather late, as the platforms have all completely filled up of people wanting to get to the rock early. Apparently, there already was a run of shuttles around 4:30am. When the trucks do arrive to the platforms they instantly fill up with people. I get invited a seat in the front of one of the trucks by a nice lady; although, sitting in the back would have been cheaper and allowed a better view of the area and the sunrise. After I arrived to Golden Rock I climbed the steps towards the top, and looked out over the view of the countryside which is vast hills covered with golden pagodas. With a large horde of people I walk to get to the main area of the Golden Rock. There are other options such as a hand raised palanquin where two men will carry you up the stairs. Once there the colorful Burmese music including gongs, drums, and xylophones, is blaring from the sound system. The music creates a carnival atmosphere where I'd expect everyone to be dancing. Families wearing traditional clothes elatedly wander the grounds.

The moment I approach the Golden rock, there are informational signs about the story of the rock, and I feel so alienated as a foreigner here. I had huge self doubt and insecurity about coming here, and what I was doing there at "their" spiritual place. Would I feel some connection to this place? I try to think of how the rock (a representation of an ascetics head hanging on the edge of the cliff by a thread of Buddha's hair) is significant to me, but no thinking would help me rationalize the trip. The second thing I think is, why are only men allowed to put gold leaf on the rock. I become annoyed and go and sit where the women are praying, and think of how I can be more connected here despite the obvious hierarchy that men are somehow able to be closer to God because they are men. I find it strange that in most respects Myanmmar women enjoy equality where they own property and can hold any job they choose. Even female babies are as celebrated and equally as educated as the sons. Although for some reason men have a special potential to become a Buddha, whereas women do not have this ability. I find a few places to simply observe and watch the other pilgrims make their offerings so I can find out what kind of offerings the Golden Rock prefers.

I have been doing meditation at home staring at candles. I take the candles and incense over to the rock and begin the offerings. A gust of wind picked up all the small pieces of paper felt over from the gold leaf and blew them into a little tornado. At first, I thought to do prostrations, bowing to the rock, but I simply wind up in a yoga baby pose. I came here to make the offerings at 11 or 12 when the sun was hottest in the sky. The Golden rock is brightly glowing. After having some water I light the candles. Having woken up at 5am to catch the shuttle, the weight of my body and head sank down into the earth. It cleansed so much energy to rest there doing meditation. My process started to clarify my purpose for arrival. In my meditation, a golden light filled my mind, and I was dwarfed by the potency of the Golden rock. At times, I felt like a spirit was trapped inside or that it needed cosmic craniosacral therapy to release it's position, lol. The face of the rock revealed itself, a shifting face within the rock morphing and playing with me. I think of the ascetic whose head is on the mountain keeping Lord Buddha's hair teetering on the edge. What is the hair? The balance? The void between falling and not falling? Suffering and happiness? The earth based Buddhist culture at the Golden rock is interesting. It's not a Buddha statue, or a temple; it's a huge rock covered in gold that represents an ascetics head.

I decide to have lunch and head back to camp. I enjoy three different types of salad; medicine salad, fermented tea leaf salad, regular salad, along with an avocado smoothie. I traveled down a trail thinking it was the way to Kinpun camp where my hotel was, or maybe to a cave nearby. Then, it went downhill to more pagodas, which were mostly nat temples, I.e. Temples for worship of a set of 37 animistic Gods that are worshipped in Myanmar. The medicine stands were selling their home made medicine oil, which I used to massage my legs wth. Unfortunately, several of these stands had illegal wildlife parts, tigers, elephants, woods, hornbills, eagles. On accident, by not knowing where I was going I ended up continuing down the mountain to the valley. It was dark jungle, silent. The perfect contrast and balance to the golden morning I had. Then, not knowing how far off I had gone I realized my mistake and soaked in the dark energy of the solitude of the valley only to climb the mountain back up again. I climbed as quickly as possible to get back in time to catch the shuttle to camp.

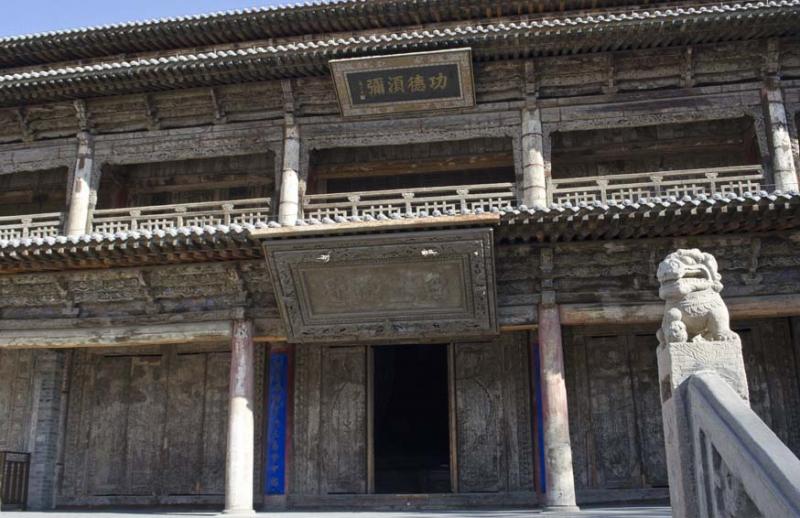

The Temple of Confucius and Imperial Academy Beijing

Among all the Confucian temples, four in Qufu, Beijing, Rehe, and Shengjing are most prominent throughout history because the Qing emperors would offer funerary rites in honor of Confucius and his followers twice a year. In the late Qing dynasty, 1560 Confucian temples were known to exist in China, with one being placed in nearly every government school (Yu, 2007). Knowing this deep history of Confucianism in China, I wanted to see for myself how the Imperial Academy and Confucius temple looked, and what kind of interesting features it might have.

The first time I had come to the streets surrounding the Confucius temple was to visit the impressive Lama Temple. There was a side street Guozijian, that I had had ventured down, but never taken much interest in. Usually taking other side streets through the other hutongs and wandering to see the various restaurants and boutique clothing shops. I also walked the streets lined with Buddhist paraphernalia, smelling the incense and hearing the Amitabha mantras being broadcast proudly from several of the shops. There are many Thankga painters sitting in the shops painting magnificent Buddhist paintings, and shops selling jewelry and other fine arts.

Now, nearly four years later, having studied Chinese philosophy for the entire Spring semester, I’m finally ready to enter the complex. The entire complex is split in half with the Temple of Confucius on one side and the Imperial Academy on the other. The Temple of Confucius, Beijing was initially built in 1302, with a total of 22,000 square meters, it is the second largest temple constructed for Confucius. The Imperial Academy, Beijing, or Beijing GuoziJian (北京国子监) was built in 1306, by the grandson of Kubilai Khan, and was the supreme academy during the Yuan(1271-1368), Ming(1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. It covers 37,000 sq meters. Emperors in imperial China would visit the academy and read Confucian books.

Upon entering the complex, I am greeted by a large statue of Confucius. I stand there for several minutes watching how people might react to such an effigy. He is standing with his hands crossed in front of him, and I notice many visitors standing on his side imitating this posture, and others stand before him with their heads bowed in order to give him respect. Many of the people honor this statue of him and seem to have a deep connection either with the spiritual world of Confucius or the philosophical world, both of which seem intertwined.

There are many myths about Confucius’s birth. On the night before Confucius was born, two dragons appeared on the roof; deities hovered in the sky and celestial musicians celebrated on the day of his birth. In addition to forty-nine distinguishing marks on the newborn’s body, his chest bore five characters that announced “Talisman of the one created to stabilized the world”. Then, as an adult, Confucius displayed expertise in identifying ancient relicts and interpreting mystical and magical occurences (Murray, 2009). His body is said to have forty-nine unusual features, which surpasses that of other deities such as thirty marks of Buddha Sakyamuni’s body (Murray, 2009). So he is seen as being an otherworldly being with qualities being more magnificent than a deity in other religious traditions, such as Buddhism.

The cult following of Confucius, and the moral ethical system which he advocated, differs from the religious expressions of China, like Taoism and Buddhism. One similarity is that there are iconic images of him that played a role in receiving sacrificial offerings, and were a standard feature of state temples, like the one in Beijing. These images have varied throughout history according to his rank and status given by the kings of different eras, such as duke, King of Propagating Culture, etc. The status and rank he was given then specified his iconic ornamentation, clothing, and head gear, as well as the number of vessels, music and dancers to be used in the sacrifices. Some later rulers wanted to elevate Confucius beyond the rank of a king to emperor, such as Zhenzong of the Song dynasty, but was opposed and unable to offer the highest level of stat sacrifice that only the ruler could offer. This same emperor tried to change the words of his title to Dark Sage, or Ultimate Sage, for which there was a change in the icongraphy perhaps like in Pingyao where there is a black faced ferocious icon. Other emperors such as the Jin Empoeror Sizong, changed the emblems on the robe from nine to twelve, and the Song emperor Huizong had nine strings of jade increased to twelve. These changes upgraded the visual appearance of the icon from a king to an emperor. Other Ming dynasty emperors increased the number of vessels and dancers in the sacrifices without changing his title. (Murray, 2009).

His ordinary life was not injected with so much grandeur, as his upbringing seems quite humble in origins, and his dedication to becoming a teacher was realized later in life. Confucius belonged to a scribal section of the service class, and served as a keeper of cultural traditions found within the state archival documents. He was a member of a shih family and spent most of his upbringing in poverty. He was forced into managerial and accounting jobs at a young age, and remained unsatisfied professionally and likely never achieved a very high position in his career. He became a philosophical teacher, and transmitter of the Tao, which established him in the history of Chinese civilization. He became a teacher separate from the political order and conveyed his visions directly to his students. His philosophy constitutes much of the “essence” of Chinese culture and his doctrines went on to become the “official philosophy of China.” (Schwartz, 1985)

Confucius advocated for a system of religious which were patterns of behavior that involved ceremonies, manners and general behaviors for the different roles one plays within the family, and all of human society ordered by hierarchical status, rank and position, as well as the heavenly realms. The definition of Li (ritual) is applied not only religious rituals and ancestors, but also living members of one’s family. Through the concrete acts of li one can cultivate an inner heart culture as well as proper behavior in family life, society and government. Jen is defined as the inner moral life of an individual that includes a capacity for self-awareness and reflection, including a submission to li (Schwartz, 1985). Cultivating a virtuous life of Jen is realized through education and training. Confucius believes in educating young disciples according to their desire for education and interest in the topics, and that a proper inner disposition must be there before Confucius can be of any service as a master and teacher. Li and learning are linked together, then jen can be attained and realized in it’s highest form of personal ideal and excellence. (Schwartz, 1985)

The first large statue in the Confucius temple is only one of many images that I will encounter through my journey in the complex. It is considered a temple in the traditional sense, and a temple is a place for worship and sacrifice, so seeing how this is constructed for Confucius I will notice the similarities and differences. Since the complex has over 700 years of history, there are many different objects and images to be discussed.

To the left and right of the Confucius statues are many tortoise steles (bixi) erected in rows up and down the corridor. These are large stone slabs that sit on the back of a tortoise and sitting under a pavilion. The top of the stele is carved with a dragon, said to be one of the nine sons of the Dragon King. Similar steles are found throughout temple complexes for Taoism and Buddhism as well, and serve as important cultural relics sharing information about historical events and calligraphic arts. In addition to the stele in this front courtyard, there are 198 stone tablets contain the names of more than 51,624 jinshi’s (advanced scholars) of the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. They had passed the imperial examnation, which was the civil service exam to select candidates for the state bureaucracy. The test was based on knowledge of classics and literary style. The exam was an important part of Chinese culture and helped to give structure to the intellectual and cultural life. By the Ming Dynasty, the highest degree of jinshi became the highest office, which was much higher than the shengyuan degree that was the initial degree, and required law, math, calligraphy, equestrianism, and archery, in addition to the Confucian classics. By 1370, the examination lasted between 24 and 72 hours and were conducted in spare, isolated examination rooms, or rooms with small cubicles. Students identified themselves by number and tests were recopied by a third person so to prevent the handwriting from being recognized. This system is the root of the National Examination that is in place today, where there are students selected from the college examination system to come to a school like Tsinghua, where only 5000 students per year are chosen out of the millions of students that take the exam annually.

After walking around in that courtyard for some time, then I entered through the first gate inside of the complex, the Gate of Great Accomplishment. Housed within this gate are several large stele with Emperor Qianlong’s handwriting on the top, as well as bells, and then there are ten stone drums The ten stone drums were thought to commemorate a military victory by King Xuan of Zhou. Qianlong wrote a poem that the number of stone drums corresponds to the ten heavenly stems; these stone drums are exceptional ritual objects that have lasted for thousands of years,”(石鼓之數符天干, 千秋法物世已少) (Yu, 2007). The stone drums are replicas of the Western Zhou dynasty, and the inscriptions on the top were recreated by the order of Emperor Qianlong.

After walking through the first gate there are small individual pavilions to the left and right hand side to house 14 important stele. The inscriptions found on these stele are often military stories, and were gifted by various rulers. Manchu rulers installed “gaocheng” stone steles with recounts of the military victories in the Guozijian’s Confucian temple. In 1704, the Kangxi emperor installed his first stele at the Guozijian. Emperor Qianlong erected four steles, all inscribed with texts in both Manchu and Chinese. In this way the Confucian temple became a monument for Manchu imperialism and not only a temple grounds for sages (Yu, 2007). Each stele has a small placard that describes where the stele came from, and whom it was gifted by and when.

There is a large glazed archway, the second gate, that was built in 1783. It was three portals, five, pillars and a roof in Wudianding style. It is covered by yellow glazed tiles, and one tablet has inscriptions written by Emperor Qianlong.

There are cypress trees which line the walkways and planted adjacent to the pavilions. It’s a very beautiful contrast between the red paint and green cypress trees. Walking towards the Confucian temple then I see there is a 700 year old tree named Chujian Bai (Touch Evil Cypress), and legend tells that during the Ming Dynasty a nefarious official named Yan Song passed by the cypress and it took his hat off, and therefor became known for distinguishing good from evil.

Climbing the steps to the Hall of Great Accomplishment, the Confucian temple, I walk past a large stone slab with dragons carved into it. I approach the building and which in appearance is very similar to the Buddhist and Taoist temples that I have visited all around China. The colors and themes are all very similar. When I walked inside, I noticed that there were no statues of Confucian within the, but there are wooden tablets with various calligraphies said to represent him and his students. The wooden tablets were surrounded by sacrificial vessels, and marble animals. New-Confucian ritualists rejected the use of icons in Confucius temples because the classical texts did not include deity worship in the sacrificial rites, and including imagery and icons would alter the character of the sacrifice and change the way that Confucius himself had realized the rituals to be performed. Kong writers stood up for the images, carefully documenting and preserving accounts of the lineage’s images of Confucius throughout the late Zhou to early Han, in order to prove the defense of icons. Then in 1392, Ming founding emperor Taizu, built a new temple for Confucius in Nanjing and ordered images to be removed and replaced by wooden tablets with the names and titles of Confucius. After that the Yongle Emperor allowed for refurbishing of the icons in the imperial academy’s Confucian temple. (Murray, 2009). Today, they want to emphasize this history by using wooden tablets. There are several informational displays with small drawings of Confucius and his students, and no other statues or paintings.

Also within the hall were many of the traditional instruments used for playing music, such as guqin, guzheng, and drums, and bells. Qianlong also used Zhou bronzes as sacrificial offerings on display on the central altars in the Confucian temples. Dacheng Dian 大成殿 (Hall of Great Achievements) during the shidian sacrificial ceremony, Qianlong offered the bronzes to Confucius. Mentioned in the edict were a ding-caldron (鼎), an yi-bowl (彝), an animal-shaped zun-vase (犧尊), a you- bucket (卣), a lei-jar(罍), a hu-vase (壺), a fu- bowl (簠), a gui-bowl (簋), a gu-cup (觚), a jue-cup (爵), a xi-washbowl (洗), and a dragon-spoon (龍勺). The emperor transformed the collectible antiquities into the ritual objects displayed on the altars of shidian ceremonies. In a sense, the group of Zhou bronzes was more like sacrificial offerings placed on an altar, rather than ritual vessels to hold food and drink offered to Confucius. Today the ten bronzes that Qianlong bestowed upon the Confucian temple at the Guozijian are in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Modern scholars believe that only three of these ten bronzes were cast in the Zhou. They assign one to the Shang and one to the Han, asserting that five others were later copies(Yu, 2007).

Imperial religion involved a cult of gods and spirits listed in the Rites of Zhou. They were serviced by officers of the court and bureaucracy and sanctioned by the Confucian canon. The court condoned specific worship at local temples according to the title of the deity. The Rites of Zhou describes five types of ritual such as capping and marriage, mourning and burial of the dead, which were common to all people. Other rites involved the royal court and social nobility such as the military rites, which brought military personnel together, and guest rituals, which the king used to interact with court nobles and lords. Finally, the auspicious rites, defined man’s relationship to the gods and spirits through sacrifice. (Wilson, 2002).

Emperor Qianlong renovated the Confucian temple in 1768, and donated Zhou bronzes, ten stone drums, and stone steles of the Thirteen classics. During the time of the renovation it was suggested to build a Biyong hall for imperial lectures as found in the ancient rites of the Zhou, and he agreed nine years later. He did this to remind Chinese subjects to honor Machu civilization preserving the traditions of the ancient Zhou (Yu, 2007). The hall is built on a square platform, surrounded by a circular mote, which is reminiscent of ancient beliefs that earth was square and heaven was round. The hall is 17.7 meters in length and width. Entering the hall, I saw the throne and armchair used by previous Emperor’s who came here to give class, there is a geometrical ceiling which is quite mesmerizing. In addition to the hall there are 33 rooms on the east and west sides of the hall. The colors of the temple are mostly a dark red, dark yellow, and black, and I found the outside of the building to be very different in terms of colors and ornamentation from other Buddhist and Taoist temples that I had visited. It is reminiscent of other unique buildings dedicated to the Emperor, such as the Forbidden City or the Temple of Heaven, but the armchair and throne were unique and bright.

After walking through the music hall, I arrive to the final hall of the journey. I walk into one large room and notice rows and rows of stone tablets. The calligrapher Jiang Heng (1672-1742) spent twelve years transcribing the entire Thirteen Classics of over 630,000 characters onto paper, and his work was recognized by Qianlong. He ordered to have the text etched into 190 stone steles and installed in the courtyard of the Guozijian(Yu, 2007). The Book of Changes, Book of History, Book of Songs, Spring and Autumn Annals, the Analects, Mencius, and other Confucian Classics. The hall is filled with long rows of stone tablets, which I walk through.

My impressions of Confucianism were expanded through my visit to the complex. It has amazing history, and I was excited to be able to visit it.

References

Murray, J (2009) “Idols” in the Temple: Icons and the Cult of Confucius. Journal of Asian Studies. 271-411.

Schwartz, B (1985) The World of Thought in Ancient China. Harvard College.

Wilson (2002) Sacrifice and the Imperial Cult of Confucius. History of Religions. The University of Chicago Press. 41:3, 251-287.

Yu, H (2007) The Intersection of Past and Present: The Aianlong Emperor and His Ancient Bronzes. Dissertation. Princeton University.

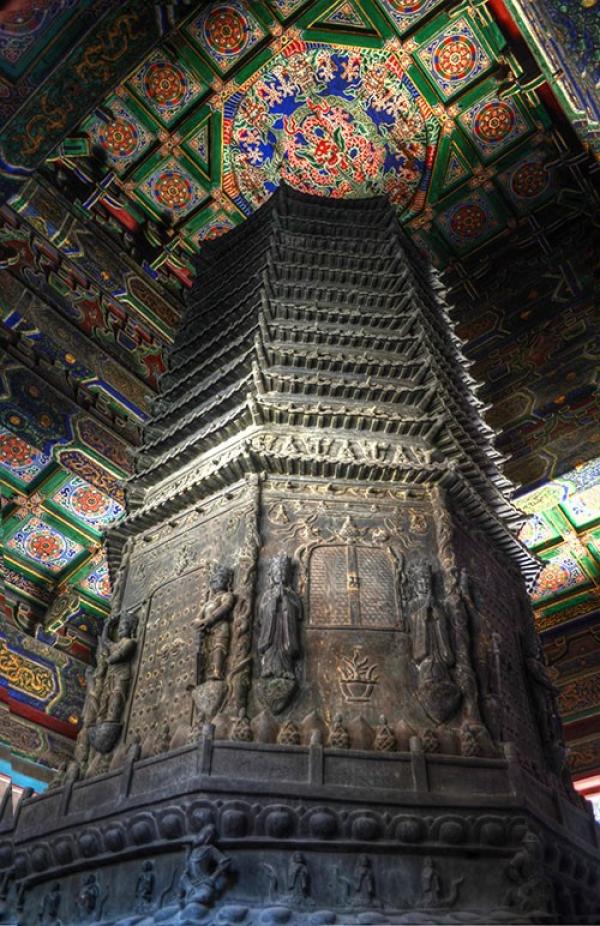

Longevity Temple (万寿寺)

I am like a sensitive bat. Moving abroad to China has been a very receptive time for me, and I frequently feel isolated as if I live in a cave. In an attempt to see through the darkness, I go alone to the longevity temple. Longevity in China is depicted by the character (寿) shòu, often times found decorating porcelain with five flying red bats surrounding it. The flying red bats appear flying the clouds on the ceiling of the entrance hall of the building. There’s nothing to say when by oneself, and everything to absorb and take in. The pagoda in the final room draws me in. It’s a five feet high tower, made of copper, lead, arsenic, zinc, silver, gold and other metals alloyed together pointing upwards in the encompassing, protective rainbow painted hollow of the temple. The small pagoda room is about the overall square footage of my current living quarters.

My situation living on a Chinese college campus has been uniquely isolating, in that the campus dormitory allowed me to have my own room. I would outright refuse to stay on campus if I had to share a room, and luckily the campus administration accommodated my request. Conversely, a Chinese master’s student on that same campus would room with 6-8 other girls or boys in a room stacked with bunk beds. The lessons in humility in what a Chinese student endures are very real, what to speak of the crowded subway, traffic, spitting, cutting in line overall, in the city of 20 million people. Quiet never seems to come easily, but patience has to, so much that awareness is an innate quality in most of the people I come across. I have been able to live a fairly ascetic life in a single occupancy dormitory, outside of which there’s a quiet courtyard where bats just happen to nest and fly.

The danger of becoming very alone in a foreign country is great. The danger of letting go and leaving everything you once knew behind is also very great. I have found that I never fully let go of the things that haunt me the most: the infatuations, betrayals, and patterns that have me caught in recurring cyclic fractals still won’t leave me, and they still show up here. Even during a nice walk through a 16th century temple, an imperial dwelling place that houses innumerable relics and ancient art treasures isn’t enough of a meditation. It takes sitting, absorbing, being receptive.

The small temple has but a small path to circumambulate the octagonal pagoda. The concept of yin and yang describe how opposite and contrary forces are actually complementary. I find the yin and yang duality appears prominently in this temple space. The inside of the temple walls (the womb of the temple) painted with bright colors, and dragons (a very yang symbol), and the pagoda itself (also a prominent yang symbol) being made from cold dense metals and stone. Very powerful for me to internalize the masculine becoming the feminine and vice versa, as both the yin and yang elements of the temple also possessed qualities of their opposite.

Tourism to the temple sites with a camera felt guilty like robbery, as if I was raiding the building. Taking photos of the Buddhas inside the temples was forbidden. At first, I was like any other tourist taking pictures, and even though I knew better than to take photos, I couldn’t resist. I wanted to remember and share my journey. I didn’t want to mimic the Chinese way of honoring the deities. I had to connect in my own way and have an awareness and intention for visiting.

Photography became another meditation on the space, to find the right composition or make some artistry out the visit. At first, staying “present” in the meditation was impossible, I only wanted to look back and be back and feel back. I didn’t want to look ahead, and looking through the shutter seemed tolerable. Everything I did in terms of travel felt immature and foolish. I became lost. The temple complexes and Chinese imperial buildings were some solace with their alchemical historical magic. I slowly got lost enough to recognize the different dynasties artworks, and recognize the deities in their different forms each rendition offering a new face, and a new mood. I see myself becoming like a deity with a golden light aura, wearing fine ornaments, exquisitely crafted. The reflections on the deity somehow managed to sink in, in many different angles, with many different shades and tones. It helped me stay present enough to notice the details, and find things that were different.

More...

Rebkong, Qinghai province

I snuck on the bus to Rebkong, Qinhai province, at 6am with a white and turquoise Tibetan shawl covering my head and face. The owner of the small hostel I stayed at near Labrang monestary warned me that due to a recent self-immolation there that they weren’t allowing foreigners to get on the bus, but he said to conceal myself and I would be fine. I wanted to visit Rebkong because I discovered on the internet some information about this small traditional thangka painting village and I wanted to visit it. Luckily it was cold enough out that the heavy jacket and scarves seemed normal, I darted my green eyes quickly around to get through the ticketing booth, and I quickly pretended to be asleep in the front of the bus for the two or three-hour journey.

The bus arrived into the area and I found myself staring and lots and lots of half finished cement apartment construction as we near the small town. The Chinese development companies were building a small city on top of this small Tibetan town. I got out of the bus and headed towards a small hotel hoping to find lodging easily here. They did not allow foreigners to stay at the first hotel I stopped at but luckily there was another place in the area with the necessary permitting. After checking in, I took a walk through the town. On my walk, I saw the newly established business malls and ranks of Chinese soliders, dressed in their standard green uniforms with a red cuff, parading in unison through the town in a group of thirty. I noticed the oppressive government as well as the Chinese business culture which had established itself in one area of the town. Many of the shops were blaring Chinese music. At this same moment that I arrived there, I was reminded of my own families losses. Suddenly, I felt a deep connection with the female monk who had performed self-immolation after seeing the drastic amount of construction there. The parcel of land I grew up on with my family on was auctioned off by my grandparents and set to be developed, and just before the construction was set to begin my brother had committed suicide on the land there. It's not the same situation at all. I don't know why my mind was suddenly drawing this parallel. I wanted to see the situation from her side too and relate to her in some way, and my mind wanted to find some meaning there. It's not the same, and my brother didn't commit suicide because of the development, but because of his own issues. He was troubled with heartache at the time. It seems like the act of self-immolation is so powerful, and the loss that the town was experiencing could be very palpably felt in the psychic ethers, and seeing the military presence there made me think seriously about my decision to arrive there. Did I need to continue hiding? Would I be kicked out? As I walked through the town with my head and neck covered trying not to be noticed by anyone, especially the police forces, and I felt a kinship with the people there who were also suffering from this loss. I felt heavy in my spirit knowing this had happened there, especially after seeing her sweet photograph dressed in the maroon robes, the entire community may have been also feeling this similar heaviness.

My interest there was in the temple complexes, and Tibetan culture, which was weaved throughout the town in the architecture and artistic touches on the buildings. There are two large impressive temple complexes, Longwu and Wutun and a nunnery. The largest monestary Longwu, is in the center of the town. I wandered through in awe of the architecture. It was different than what I thought it would look like. I had only been in China for 6 months, and the temple construction I had seen up until that point was by Nepali and Tibetan sculptures and painters in America, or Chinese temple construction in Beijing. So, the first time in the middle of a large Tibetan monestary complex was mysterious, and I had wanted to see all of it. Then I wanted to know more about how to tell the difference between the buildings in the different school of Tibetan Buddhism, such as Black hat, Red hat, or Yellow hat, which each had definite features on the buildings.

There were many different temple buildings that opened according to the different schedules of their caretakers. A few times I felt lucky to track down and find those with the keys to be let inside, and other times I had no such luck. Some of the temples seemed closed for the entire day and others told me to come back at certain times. I knocked on doors trying to get keys to get inside and be alone in some of the temples. Sometimes I was lucky, other times, I was left wanting. I must have seemed eager, and almost demanding to the monks who held the keys. I was also being kind of sneaky, taking photographs and working covertly to capture this place in my camera so I could share the magic I had found with everyone.

The temple for Tsongkhapa, a prominent teacher from the Gelug school of Buddhism, was especially ornate, with a three small tiers to the temple building, each a different layer of paintings, reaching to the top of the 30-40 foot deity which had a small photograph of the Dalai Lama enshrined on his lap. Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), was a buddhist scholar who led a renaissance of Buddhist teachings, and is regarded as a reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Vajraprani and yet did not display any magical powers yet advocated for teachings of pure virtue and lived his life as a role model. The dieties of Maitreya, future Buddha, or Avaloktisvara, the Goddess of Mercy, were studded with gems and embossed with several metals, and the elaborate story paintings of Guru Rinpoche, and sophisticated decorations created contained spaces for meditations and spiritual experience to manifest itself in the heart. Multicolored quilted silk decorations hang from the tall ceilings nearly touching the meditators. I walked slowly through the area from smaller temples to the bigger temples up to the top of the hill, following endless lines of prayer wheels to spin as I walked. Every pillar covered in cloths and paintings. Through stairwells up to the rooftops, circumambulating the deities at the top of the temples, being blessed by tiny Buddha's hiding in all corners and levels of the complex.

During the walk, I met a nice young man. He looked very modern, wearing a down jacket and carrying a Nikon camera around his neck. He told me in his broken English that he is from Rebgong and that he is a painter and a photographer. He got out his IPAD and began showing me the photographs of the area that he’s taken which are bright and well composed. He was an impressive photographer. Then, he began to show me pictures of the Thangkas that he had painted, which are masterpieces of the arts, black background with think gold feather think brush strokes, white background with full color depictions of gods and goddesses in the Buddhist pantheon. It was hard for me to believe that he was really a painter and not a young sales guy repping for some old man. It actually had taken me several months of getting to know him before I actually believed him, several months later, when he had effortlessly sketched on a canvas a small deity to paint in myself. His original story to me was that his father was a painter, and his father’s father was also a painter who worked for the Panchen Lama. He told me that he began training for painting when he was 6 or 7 and was trained for his entire life until now, and he’s 25. The paintings he produced, although similar to the others in the area, had been recognised among several arts circles and societies which he hoped would one day actualise his dream of going to Europe to study despite strict Chinese laws about not giving Tibetans passports to get out of the country. There are few people who had achieved his level of mastery and he was getting all of the proper recognitions in place. We spent the day leisurely walking around the temple complex together and taking photographs. We hardly talked while walking around and he tried to show me a few of the areas I would have missed had a local not wanted to show me around. I gave him my phone number and email excited that he was planning to come to Beijing soon. He walked me back to the hotel and we said goodbye.